‘This library has stood for over 200 years, through two revolutions and the Mexican Civil War’- a man with orange tinted aviator sunglasses announces to a packed auditorium. Thus I imagine we are in safe hands for the moment.

The opening ceremony of the Area Gris International Jewellers Conference has been blessed with a buzzing sense of anticipation and fervour, as if there was a revolution of another kind brewing within Aztec style masonry. Waking up to Mexico City’s petroleum laced air is seldom a refreshing experience, but 10 AM at the Biblioteca de Mexico played host to a carnival of enthusiastic introductions, greetings and a few ecstatic reconciliations. The organisers who are among friends and colleagues appear to have devoted themselves religiously to the smooth running of this symposium.

Once the room is filled, we are welcomed and thanked by Valeria who appears to be steering this ocean liner of cultural co-operation ‘We want to establish links between developing areas’ she tells us. Her associate honours the guests by announcing this event ‘the most ambitious project yet’.

We begin a series of informative talks revolving around the open theme ‘What does it mean to us? Jewellery, Identity and Communication’. Manon van Kouswijk of the Rietvald Academy, Amsterdam starts with a lecture entitled ‘Grey Matter: No Brain No Gain’. She speaks seriously of childhood streaked with grey of all kinds. As head of the Jewellery department for three years, she poses many questions to the international audience. ‘What can Europe contribute to the world of contemporary jewellery?’ strikes at the heart of her concern that jewellers seems to be content with satisfaction and safety inside their own ‘bubble’. With this, she reminds us that jewellery is often more like ‘The Hunt for Treasures’ and asks us if a wider audience can be reached without a compromise of any kind. With suitable aplomb, Van Kouswijk closes the presentation with a poetic gesture- ‘Jewellery can fly all over the world’

As Caroline Broadhead of Central St. Martins College, London steps to the stage, one wonders how many Latin American delegates would have expected a presentation of such a British calibre. Yet we are offered a truly tropical display of images. Jewellery, technology, visual and performance art all point towards profoundly philosophical question; one of visual interaction. Briefly reminding us of children’s games that refine our ways of seeing the world and showing a simple piece of magenta optical art which once viewed, creates a green ‘jewel’ on another’s body, we are invited to expand our current ways of perception, beyond obvious aesthetics. Broadhead makes an ambitious link between Jewellery and sight in the etymology of the word ‘mask’, from the Greek meaning an amulet to protect against evil. In a city where the blind appear on the streets more frequently than in many European countries, she offers us a bold discourse on the value of looking from many points of view.

Dr. Clemencia Plazas of Colombia National University informs us on the geography and history of metallurgy in Latin America, with a special emphasis on precious metals. Not surprising as a former director of the Gold Museum, Bogotá, she offers us a wealth of information on silver but mainly gold. This, she tells us was prized by pre-Colombian civilisations because of its likeness to the sun, which they worshipped as a prime example of balance and cycle. Their gold medallions are described by historians as an ‘expression of vacuum’ and portrayed vibration in the metalwork of the pieces. With a nod to the previous speaker, she shows us examples of Optical Art dating to the 8th century AD, perhaps hinting that many contemporary attempts at such art are echoes of the achievements of conquered civilisations. Ending on a light note and reminding of alternative locations for jewellery, Plazas has saved the best for last. Golden ornamental coverings, like abstract drinking horns, for male genitals once served to symbolise hierarchy and social position. Similar looking breast coverings appear to be property of Madonna, except they were found in the Sinu region of North Colombia, from 300AD. However, as the pieces appear closer thematically to notions of childbirth, we are reminded of the immortal significance of life and death in jewellery.

Ramón Puig Cuyas, head of the jewellery department at the Escola Massana, opens his talk on the use and meaning of Materials for Different Cultures by quoting Sophocles on the purity of the material. He describes jewellery as a cultural phenomenon, the language of which is loaded with magical symbolic properties- and a link to survival. He further suggests that as far back as 70,000 years ago, Jewellery would not have stood just as a symbol of power; an artist makes an investigation into the order of the world, conveying discoveries the viewer. Finally he mentions that the modern jeweller breaks so many rules in their creative practice that identity in the work is hard to find, yet it is often composed of different emotions.

Clemencia Plazas’ second talk was centred on more spiritual aspects of the Pre-Colombian passion for gold. The nature of opposites and cycles, she tells us, contributes to their sense of universal balance. We are shown images where gold and silver are placed together equally, where gold is plated by silver and of the metals’ use to secure a route to the afterlife. Revealing to us that they worked in also in platinum and red gold, she closes by making a marked distinction between two regions of Latin America: one which worked with the metals in solid state, and one which worked with them in molten form. Plazas has supplied us with an important grounding in the ancient history of Latin American jewellery with hint of insight into its stylistic relevance today.

The final talk is given by Dr. Damien Skinner, art historian and freelance curator from New Zealand. His presentation concerns a single piece of highly significant jewellery by Warwick Freeman- the ‘Tiki Face’, a brooch that has obvious tribal links but with a simultaneous sense of contemporariety. He explains with clarity of international intent the history behind the culture of the native Mali people of New Zealand. Their ‘Hei Tiki’ figurines which, like some of the Aztec idols, come with significant spiritual power are made of jade, a material of a ‘problematic’ nature because of the historic colonial conflicts behind it. Skinner goes on to relate a part of 20th century NZ jewellery history when pieces were made entirely out of bone, stone and shell as part of a rejection of European jewellery standards. Nonetheless, we are left with a sense that Skinner is an ambassador from a country where old and new, visitor and host are continually learning to cohabit. Perhaps his approach will become a hallmark of future contemporary jewellery, where collaboration across cultural and national boundaries will become standard practice.

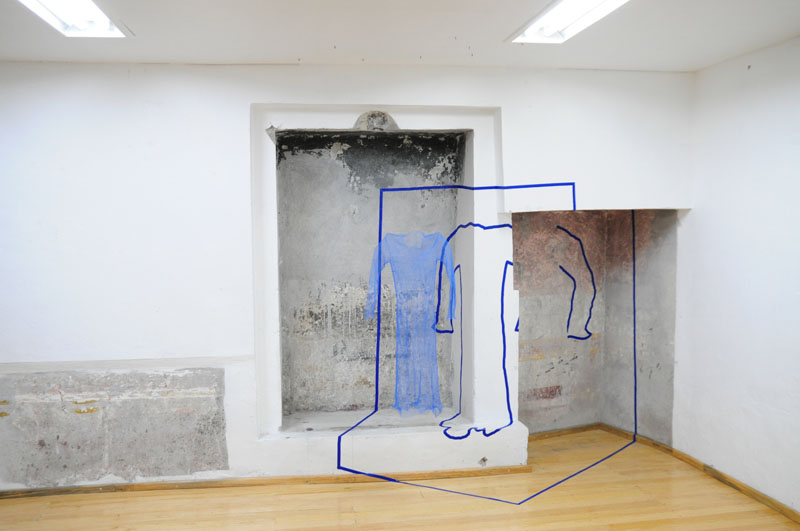

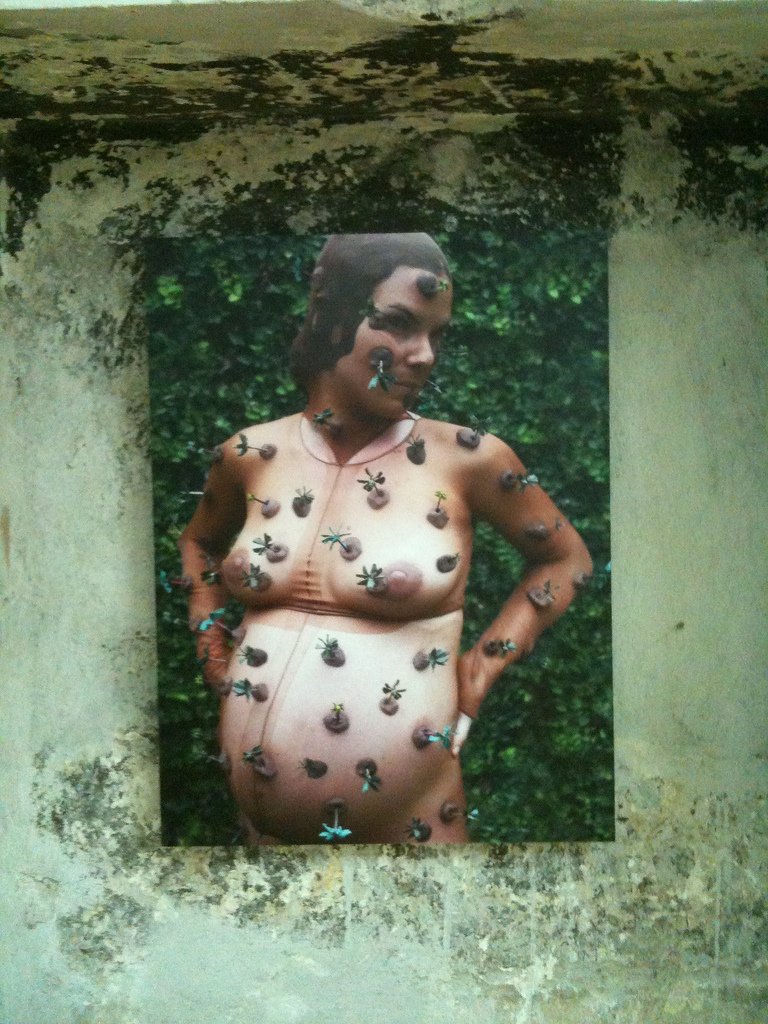

Gray Area Inaugural Event

Ex Teresa Arte Actual

Images of the exhibitions Ultrabarroco (Benjamin Lignel & Alex Burke, Estela Saez & Eugenia Martinez, Cristina Filipe &Heleno Bernardi) and DesCubierta (Raquel Paiewonsky & Catherine Broadhead)