|

|

|

|

Mobile Matrix (first image), a piece made by Mexican Artist Gabriel Orozco with the graphite sketched bones of a long fin whale found on the south west coast of Spain is displayed at the Biblioteca Vasconcelos in Mexico City. Dark Wave (second image) is a second version of the first whale made for the White cube in Mason’s yard in London. It was not possible to use a real whale skeleton for this pieces, so a replica was commissioned to the Spanish company Factum Arte. Hola, Valeria! I love the works of Orozco! Here are more bones…

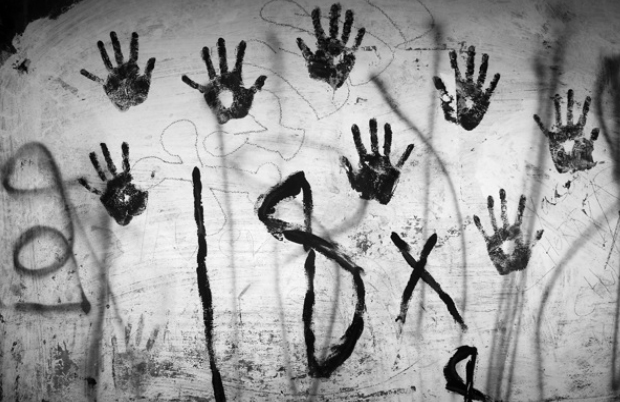

Cildo Meireles is a kind of pope for me… Mission/Missions ‘I wanted to construct something that would be a kind of mathematical equation, very simple and direct, connecting three elements: material power, spiritual power, and a kind of unavoidable, historically repeated consequence of this conjunction, which was tragedy’, Meireles has said. The resulting work comments on the human cost of missionary work and its connection with the exploitation of wealth in the colonies: the ceiling is composed of The missionaries hoped to save the Indigenous population from what they understood to be the most savage of practices, cannibalism. As Paulo Herkenhoff explains, ‘In a plea to eradicate cannibalism, the missionaries offered in exchange the Eucharist and the Holy Communion – the consumption of Christ’s body.’ Yet the missionaries’ desire to absorb and replace the beliefs and practices of the Indigenous people itself constituted a form of cultural cannibalism, one culture or civilisation absorbing another. Some days ago I learned, with great sadness, about the death of French-Spanish film maker and photographer, Christian Poveda. I had the pleasure and honor to meet Christian some years ago in Mexico. Sitting in a privileged garden in the mountains at the Gulf Coast of Mexico and drinking tea with rum, he talk enthusiastically about the project he was about to start in El Salvador. Christian Poveda devoted his work and his life to portray social conflicts all over Ibero-America. He spent over three years in El Salvador, working with La Mara Salvatrucha and La Mara 18, two rival gangs composed by Salvadorans, Hondurans, Guatemalans and Nicaraguans and that have held a ruthless war for over a decades. Over 14 thousand forgotten youngsters show a tremendous rage through their tattoos and the complete devotion to their gang, that comes to replace family. They are heirs to the gangs formed in the United States during the 1980′s by the Salvadorian immigrants that flew from El Salvador during the civil war. Born in the Ghettos of Los Angeles, the legend of the Maras became stronger in Central America as the illegal immigrants were deported back to El Salvador. Through his film, La Vida Loca, presented at the San Sebastian Festival last year, Christian documented the personal and everyday life of some members of these gangs, masterfully portraying the violent phenomenon that has been imported from the USA. As commented by Mexican photographer Ulises Castellanos, when talking about his work Christian insisted on transmitting the idea of how artists should get involved in their own work and always be honest with the individuals that were the object of their obsessions. He was committed with his work, with the people we worked with and with the world in general. Christian used to say that it was that dedication that led him to become a paternal figure for the gangs; kids, who were mostly orphans or abandoned by their parents, found a generous person in him. He visited them every day, just stopping by to find our how they were doing and, this, establishing a unique bond. On September 2009, Christian was shot to dead in the Salvadorian barrio of Tonacatepeque, 16 kilometers to the north of San Salvador. Watching his film has been a bitter-sweet experience. The film shows the unique and utterly beautiful way in how Christian Poveda captured images and emotions and, at the same time it shows the crude and desperate reality of El Salvador. There is also the pride and satisfaction of seeing a friend’s work so masterfully accomplished, but seasoned with the sadness of knowing that he is no longer here.

You can visit the homage exhibition, put together by his Mexican Students in cooperation with Zona Zero: http://zonezero.com/exposiciones/fotografos/poveda/index.html

Adieu chère Dear Artists and visitors, Thanks to you all, the WGA Blog has become a successful project. We are all glad to see that everyday, the WGA artists engage in interesting conversations, while new visitors from all over the world keep joining this blog to learn about the personal process involved in jewellery-making. Following this line of collaborative work between artists from Latin America and Europe, we take advantage of this blog to introduce a new group of six artists, selected by Mexican curator Valeria Vallarta who will work, in the following months to develop a small exhibition to be presented at the Gray Area Symposium’s venue, Ex Teresa Arte Actual. In Ultrabarroco, visual artists and jewellery-makers Eugenia Martinez (Mexico), Estela Saez Vilanova (Spain), Cristina Filipe (Portugal), Heleno Bernardi (Brazil), Alex Burke (Martinique) and Benjamin Lignel (France) explore and discuss the complex processes and relations between ex-colonies and ex-colonizing countries, both from an historic and current perspective. Each artist will create a jewelllery piece as a result of their dialogue. This exhibition is being developed within the frame of the Ex Convent of Santa Teresa la Antigua, a Carmelite convent built in Mexico City in 1616 and will be inaugurated in April 2010 in Mexico City. We wish to welcome the Ultrabarroco artists to this blog. Dear All, tomorrow I’m going to meet Karin Seufert who is coming to São Paulo after a trip to the Amazon region and Rio de Janeiro. We decided to organize a workshop in the countryside of São Paulo and WGA has been a sort of stimule for it! We are going to discuss/research materials, whether its identity is connected to a place or not! Karin along with Tore Svensson are bringing materials from Sweden and Germany and the participants will bring their own. I will post later pics about this workshop! If any of you are also interested in coming for a workshop, let me know! You can now subscribe to our blog using your email account! Check the link on the right-hand side, just below our Clustrmap. There was never any more inception than there is now, Walt Withman

The locomotive passes in front of us; metal wheels screeching loudly. The travelers disseminate along the train tracks. They are ready. They run along with the train. The women go first, taking the younger ones with them. Some of them stumble and fall down. Some jump and start climbing. In the distance I can see them smile. They made it, they are alive, they are on. The ones left behind can breathe now. They are disappointed, but they are also alive. They go back to their sheltering bushes, to wait for the next train… In the last years, my work has circled around the topic of migration in an attempt to deal not only with the socio-political aspects that it involves, but also with the deep personal processes experiences by people who are forced to migrate. I would like to present to you some images of to of my latest bodies of work. For the first series, Migracion, Suenos y Esperanzas del Sur (Migration, Dreams and Hope from the South), I accompanied undocumented migrants from Central America and Chiapas (a state in the south east of Mexico), both experiencing and recording their journey to the border of the United Sates . The second series, Lista de Articulos para un Viaje al Olvido (Travel Gadgets for a Trip to Oblivion) is a photographic inventory of the objects left behind in the Mexican desserts by migrants on their chase of the American Dream. Working on these projects was for me an intense and emotional journey, that placed me in the midst of the dramatic reality of forced migrations. I could witness how this appalling experience brings out the extremes of people: from the strong will to have a better life to the solidarity among the travelers and the people they encounter trough their journey; from the pettiness of the governments that look over the reality of the migrants, to the meanness of the people that traffics with their dreams. The migrants go through a long and painful journey. Hope grows on the lonely landscapes they cross, fed by the sweat, the hunger, the fear and strength of those men and women. Their peregrination forces us to review reality and become more conscious of injustice and inequity, exploitation and racism. Forced migrants from all over the world can only live day by day, holding on to a future that they don’t even know if it is there. They show us the saddest face of global mobility and take us to reflect upon the world we live in. You can view more of these series at: www.loscaminosdelmigrante.blogspot.com

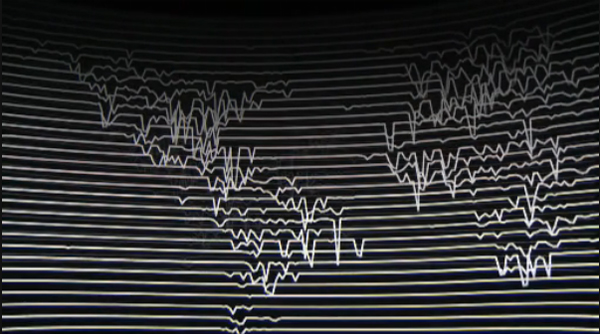

Image taken at the Terre Natale project, Cartier Foundation Human migration is the movement of people from one place in the world to another for the purpose of taking up permanent or semi-permanent residence, usually across a political boundary. Migrations have occurred throughout human history, but they have never been faster and more massive than in this century. Today, over 170 million people live, temporarily or permanently, outside their country of origin, according to United Nations figures. While some of us deal with the luxury problem of choosing where to live and have the means to exercise that choice, the vast majority of today’s migrants have been forced to migrate. One of the negative effects of globalization is the exclusion of more and more people from meaningful participation in the market economy, and thus the exclusion to have a dignified life. Migration for most migrants is less about seeking a better life than about having life at all, simply seeking survival. Art as social commentary is a major theme in modern and contemporary art. Artists often assume the roles of reporter and analyst in an exploration of the nature of society. Always at stake is the artist’s wish to uncover the workings of society and draw conclusions for understanding it more effectively. Art that falls within this theme is often critical of political structures seen as harmful, but it also celebrates the achievements of human communities and can poeticize everyday life. Its ultimate ideals are to preserve what is good and to condemn what is threatening in hope of a better society. We have invited to this blog some artists whose work deals with migration and its impact in the life of all of us. They hope to share with WGA artists and audience their views on this matter. Through their work, they explore how human migration impacts population patterns and characteristics, social, cultural and personal patterns and processes, economies, and physical environments. Mexican photographer Luis Aguilar presents a series of pictures that show the journey of Central American and Mexican illegal immigrants to the United States. The U.S.–Mexico border has the highest number of both legal and illegal crossings of any land border in the world. Luis Aguilar joined a group of travelers and accompanied them from the south of Mexico to the United States, bravely and masterfully documenting their journey through the country. As people move, their cultural traits and ideas diffuse along with them, creating, modifying and enriching cultural landscapes. The artist we have invited to present their work in these pages are able to portrait with a critical and skilful eye, the situations that force people to migrate and the way their lives and deaths change our world. We hope that you will be inspired by their work. I have been away for a long time. But nothing seems to have changed so much or has it? I always think like that when I come home after a stretch of time away from the daily routines. Sometimes every day life does not seem to fulfill the hope in the future, it may even seem monotonous, an avoidance of thinking in a better world. If you think like that, you may wonder what has happened in world history: were the lives of people same as mine hundreds of years ago? Has there not been any changes evolving from daily life? Amongst the things that seem to have changed, the myriad of little things that move without us noticing them, I found a couple of events that renewed my expectations in the change that is to come. These two findings refer to the ways in which we look at the others (and by reflection, the way we look at ourselves). Some weeks ago, while preparing the last exhibition I made, which dealt with the obsession with the death in the work of Mexican master artist José Guadalupe Posada, I found myself trying to understand the times he lived in. A century ago Posada was the eye that saw for the many: the artist who looked around him into the daily lives of his peers and fellow countryman, to the folk on the street. Posada lived and worked amidst the first revolution of the 20th century, the Mexican Revolution. During his daily life, working from a small print shop in downtown Mexico City, he used to draw eight to 10 plates a day. These plates recorded the lives and dreams of the many but also the private lives of the few. Posada filled the gaps in the imagination. These gaps exist between our life and the endless possibilities of living. In his lifetime Posada draw more than 20 thousand images with his own hands. Sometimes inventing stories and characters, as the famous lady of the death, La Catrina; a cartoon that represents a radical departure from the European Vanitas paintings (whose theme is the vanity of a monotonous life), which transforms dead from as something static and anti esthetic into a living caricature of dead. In Posada’s hands death became a paramount image of life. And while he was transforming daily life into a promise of the future, by making us imagine the endless possibilities of death (both, within life and after life), Posada became a chronicler of the world around him. When you realize this, you may think about the powers of the artist, the secret potential that his art is bestowed with. Then you slowly realize that death is not to be feared or avoided, because it is part of life and it fits perfectly in existence. We want to die and be born again in the imagination. After the opening of the exhibition of Posada’s prints in Rotterdam, I read on the paper that 35 thousand people flooded the British Museum to attend the opening of the Mexican Day of the Dead festivities last November 1st. A date when people all over Mexico celebrate they deceased by visiting the graveyards and staging altars in their homes ( at the center of their daily lives) devoted to them. There is no sadness there but a exhilarant celebration of the coming of the death to their homes. When I learned so many people visited the British Museum in only one day, I stopped to wonder. What is it that makes dead such a popular subject in postindustrial Britain? Perhaps the exhibition and performance attracted many Britons because our economic system has rendered life into a mimic, fearing pain and death, which are both part of life; or perhaps because our lives have become dull and empty, where the capitalist offer of consumption cannot fulfill our desire to transcend. November is the most significant time of the year for Mexicans because it is the period when they concentrate, by means of ritual, in that which is hold dear to them, on that which makes them feel a sense of community with their peers and with those who are no longer here but remain present by means of invocations. By virtue of the legacy of one man, Posada, this tradition has become available to other cultures. And thus it has come to seize the attention of other cultures, where the need for change and transcendence is weakening. No culture can remain isolated or unchanged by the ravages of time. And when a culture needs that of change is not coming from within it is from abroad that it looks for an answer. Mexicans have become masters of that swaying movement, from within to outside, in search of themselves and in need of understanding the diversity of existence. The first collector was a dead human, buried within his precious jewels and daily objects. The meaning of his or her life was buried with him/her in order to facilitate his journey into the far beyond. The objects he wore and became attached are tools of memory, the means to find the way back to his people, as the indigenous traditions believed it should be. When thinking about jewelry, as transitional objects that help us communicate and remember, do we think of dead as the end or just as a new stage? Watch the l the event at the British Museum at: I loved what you wrote!! Bye!!

Dear All, There are more images of this workshop that had also Tore Svensson, in the site www.njoia.com A few weeks ago, during a State visit to Mexico, Prince Willem Alexander from the Netherlands, was heard saying in Spanish: Camarón que se duerme se lo lleva la chingada (sic). He was addressing an audience of politicans and bussiness people, in an official speech about water technologies. After the explosion of laughter from the audience, his facial expression indicated that he did not seem to grasp the full meaning of the word he naively used (the Mexican proverb he quoted says literally: A shrimp that sleeps is washed away by the tide.) La chingada (as a femenine noun) is imbued with cultural significance. Whatever the linguistic meanings, which run the full gamut from fuck to sick, great joy to deep sadness, the term is never used in the media or public speech, especially not by power brokers. The word and its countless variatons do appear in the movies, novels, poetry, visual arts and popular crafts. La chingada is part of the people´s language, the street wise resource to name something that otherwise is hard to grasp. Although the Dutch media reported the incident as a curiosity or the clumsiness of burocracy, a minority focused on the intricacies of cultural translations. this is the point I would like to make here. The translation of the prince´s speech was adorned by a piece or rethoric in a language that nobody understood, but they thought they knew the meaning of La Chingada , in the end turning a prince into the laughing stock of the gentiles. As I was reading the posting by Christoph Zellweger in WGA dedicated to Jorge, I thought again about that problem. Christoph argues that Jorge Manilla assumes that people will understand the subtleties of his images or objects, by referreing to the cultural background that informs them. Having worked in exhibitions for years now, I found myself more often than not puzzled by the ways people interpret what they see. Communication or transmission of information is indeed complicated by the fact that people who communicate assume that the others, the receivers, will understand their meanings passively. The usual is the opossite: people interpret all the time, but they do it from a cultural and personal platform unbeknown to the speaker. As artist and cultural communicators, I believe that we should take for granted the impossibility to translate the experience of art as such or language as metaphor. Or to put it in Cristoph Zelleweger words: art is tool for people without language. Literal meanings do not exist in art. Obviously politicians and people in places of power depend on interpreters and translations, and when these fail they become aware of the communication dilemma: it is risky to try to use a word or a sentence which is deeply embeded in a regional significance. Artists do seem to have the gift to apropiate meanings; they can change them to their own interest and transform their meaning. But not always… how many times you found yourself baffled by people who think that your works are something completly opossite to what you intended them to be, even at the point of become insulting or degrading? Misunderstanding and its consquences are our daily bread, trying to work around them or even leave the door open to build it into your work can be a healthy attitude.

|

|

|

Copyright © 2024 Otro Diseño | RSS |

|